The most well-known medical discovery involving fungi is probably penicillin, but fungi’s potential in healthcare goes way beyond that. As technology advances, so does our ability to take full advantage of fungi. Scientists are now unlocking a new and surprising use: healing human skin with mycelium.

Mycelium is gaining attention as a biocompatible, sustainable material for wound care and even regenerative medicine. Recent research shows that mycelium can be processed in different ways depending on its intended medical use, from bioactive wound dressings to advanced skin substitutes.

What is Mycelium?

I’ve touched on mycelium in my previous posts, but today I want to give it the spotlight it deserves and dive more deeply into why it’s such a powerful material.

Mycelium is the root-like network of threads called hyphae. While mushrooms are the fruiting body of the fungi we see above ground, mycelium is the real body of the fungi that extends through soil, wood, and other organic material. Through this intricate web, fungi form symbiotic relationships with plants and support their growth through nutrient exchange.

But mycelium isn’t just ecologically important. Its structural properties make it promising for biomedical use. These dense, fibrous webs are naturally:

- tough yet flexible

- Porous, which allows air, fluids, and nutrients to pass through

- Interconnected, forming a 3D structure similar to the human dermis (collagen-rich lower layer of skin)

What makes mycelium especially unique is its composition. It’s rich in biopolymers like chitin and β-glucans. Chitin, typically found in the exoskeletons of insects and the cell walls of fungi, is known for its structural support. Meanwhile, β-glucans are known to boost the immune system and stimulate collagen production, both of which are vital for wound healing.

Unlike synthetic materials that need to be molded, mycelium grows itself into shape. It expands naturally, adapting to the space and conditions around it. All these qualities make mycelium an excellent candidate for next-generation skin substitutes.

Different Forms of Mycelium in Healing Wounds

1- Mycelium as a biological scaffold for skin regeneration

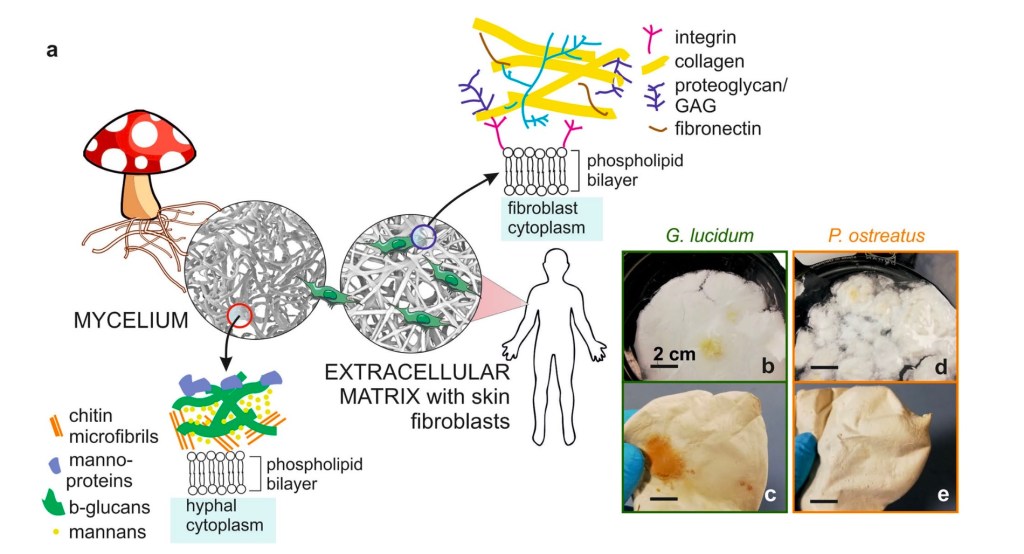

A recent study looked at how the mycelium from two edible mushrooms, Ganoderma lucidum and Pleurotus ostreatus, could be turned into sheet-like materials to help skin wounds heal. The fungi were grown in the lab for about 20 days, then the mycelium was collected, sterilized, and pressed into thin, scaffold-like sheets. These sheets were analyzed for their structure, thermal stability to understand how they might interact with cells. The team then tested the materials with human skin cells in the lab to check if they were safe, helped cells grow, and stimulated the expression of healing-related genes like collagen. And the results were promising: extracts from these mycelia were non-toxic to human skin cells and even boosted their metabolic activity and gene expression. (If you want to read more about this study, make sure to check out this article).

Image credit: Adapted from Antinori et al (2021), Advanced Mycelium Materials As Potential Self-Growing Biomedical Scaffolds

This image from the study linked above clearly illustrates the structural similarity between mycelium and extracellular matrix of human skin cells. On the left, the mycelium’s cell wall is shown with chitin microfibrils and bioactive molecules. On the right, the ECM is shown with collagen, proteoglycans, and integrins. Both sides highlight a layered, structured matrix that supports interaction with cell membranes. This visual comparison helps us understand that mycelium doesn’t just cover a wound like a bandage, but it also provides a biological environment that actively supports skin cell regeneration, much like the body’s own healing matrix. Frames b through e depict the change in mycelia after simple processing. They seem to have become smoother, more flexible and sheet-like, just like human skin.

Another study worked with mycelium from Aspergillus species to create skin-like scaffolds. The fungus was grown into soft mats made of chitin and glucan, then treated with a chemical to strip away surface proteins that might trigger immune reactions or harm blood cells. The final product was a thin scaffold that mimics human skin. It was safe for blood contact, allowed human skin cells to stick and grow, and slowly broke down over time. While the researchers only conducted in vitro (outside a living organism) experiments, the developed scaffold will eventually be tested in vivo experiments as a direct graft onto the wound.

These studies along with many more are showing just how promising mycelium can be for wound healing, and are spurring a new wave of innovation in the field.

2- As wound dressings

Some researchers are developing mycelium-based hydrogels by extracting biopolymers like β-glucans and incorporating them into gel formulations. These experimental gels may one day be applied directly to wounds (like a cream or spray), protecting the area from microbes, retaining its moisture, and help with the release of healing compounds.

A research proposal outlines a plan to test whether mycelium can be an alternative to common medical gauze products. The efficacy of traditional gauze products remains limited due to several factors: They can shed fiber into wounds, and they don’t actively help with healing. Mycelium has already shown promise for wound repair, but researchers still don’t know much about how well it blocks bacteria. This study aims to test whether mycelium gauze blocks bacteria as effectively as the current products. To do this, mice will be given third-degree burns on their backs and treated with one of three options: regular cotton gauze, Acticoat antimicrobial gauze, or mycelium-based gauze. All wounds will be exposed daily to Staphylococcus aureus, which is a common infection-causing bacterium. Researchers will swab the wounds daily for 28 days, plate the samples, and count bacterial colonies.

While this proposal hasn’t been approved yet, researchers predict that mycelium gauze will outperform cotton and Acticoat in blocking bacteria, due to its small fiber diameter and dense, porous structure. If successful, mycelium can be used for a more bioactive wound dressing. Further research testing this material on humans, instead of mice, is also underway.

Conclusion

Traditional wound healing focuses on basic care like keeping the wounds clean, covered, and protected. This often involves simple gauze and antibiotic dressings, and ointments. These tools work, but they’re passive: they don’t actually interact with the biology of healing.

Mycelium-based methods are a big step forward, moving toward bioactive, regenerative healing. Instead of just acting as a cover, mycelium helps the body repair itself. Its structure is a lot like the natural framework in human skin, giving new skin cells something to grow into. In addition to their greater efficacy in wound healing, mycelium-based products are eco-friendly. They don’t demand the use of plastics or energy-intensive manufacturing.

That said, mycelium-based products are still in the experimental stage and haven’t made their way into everyday medical use yet. Researchers need more studies to figure out the best ways to use them and to confirm they’re safe in the long run.